a nation conversation

with: clemens habicht

from: the play group

There’s passing the time, and then there’s spending it well. The objects made by The Play Group belong firmly to that second way of living. They’re meaningful and lasting, inviting us to pause, to connect—and, of course, to play. As they put it, they’re a “celebration of artists, form, and function.”

Co-founded and creatively lead by artist and director Clemens Habicht, The Play Group is best known for its wildly artful puzzles. While their aesthetic qualities are obvious to all, their real power lies in what they make possible: they slow life down and bring people together.

Habicht’s own designs set the bar high early on. His original, now iconic 1000 Colours puzzle is deceptively simple but profound, formed through a deep understanding of print, colour, and craft. As The Play Group business has grown, it has expanded its creative horizons with contemporary artists like Gemma Smith and Jonathan Zawada, inviting new hands and ideas into the mix while staying true to its central promise: make things that are beautiful, engaging, value-driven, and long lasting. Heirlooms of time. Connectors of friends and family. And, frankly, ultra cool objects for the home.

Here, Clemens reflects on the quiet spark of connection and creativity that inspired The Play Group, how its ambitions have evolved, and the way the project has grown in tandem with his own life—as both an artist and a parent, designing for togetherness and purpose, one piece at a time.

Clemens Habicht

"Puzzles have been around for centuries. They were originally tools for learning—maps, math, memory. It’s only more recently they’ve become a form of leisure, something we associate with quiet time."

The Puzzle of Connection

Clemens Habicht’s love for puzzles begins with the desire to connect. As a young adult, he was living abroad and alone in Berlin, and was seeking some familiar experience that would make him feel more at home. He soon began to spend Sundays with his great-aunt, working on puzzles at her dining table.

“She used to frame every puzzle she finished" he says "They were like these soft trophies—small, patient victories that became part of her home.”

These visits were not about sparking conversation or activity — they were simply for sharing time. Forming a humble, human bond, that spanned generations, interests, and cultures, made possible through this simple shared activity.

“We didn’t have loads to talk about—we were from different worlds, and while I spoke German, the conversations were a bit stilted,” he says. “But sitting next to each other, working slowly on the puzzle, there was this really easy companionship. It didn’t require anything of us except to be there, in the same space.”

That quiet ritual would set the foundation for The Play Group, but its real inception came years later, on a family trip to the Pyrenees with Clemens sister and her young child. Expecting to be snowed-in and needing to have something to do indoors, Clemens brought along some puzzles, including one of Mont Saint-Michel. In doing this puzzle, what captured his attention wasn’t the monument—it was the sky. The gentle transition of colour drew him in.

“There was this very subtle gradient—from blue to pale grey to pink—and placing each piece felt deeply satisfying. No box image required. Just colour, logic, and attention.” The idea of a gradient-only puzzle took hold. “It was more meditative than anything I'd done before. It gave me a kind of quiet joy.”

What followed was a period of tinkering and testing. Back home, Clemens began developing prototypes for what would become the 1000 Colours puzzle—a thousand-piece grid where each piece is a single, distinct colour from the full CMYK spectrum. “If you want each piece to be a single colour and for the whole thing to be mathematically precise, it starts getting really technical.”

Precision, Patience, Playfulness

The challenge to transforming this idea into an object lay in the production process. Making a puzzle is, technically, easy. Making one where each piece subtly shifts in colour with no defined image to fall back on? Much harder. “We tested loads of prototypes. You can send any image to a printer and get a puzzle back, but for this to work, each colour needed to align exactly with each cut piece. The sheet can shift slightly—maybe two millimetres—before it’s cut, which creates visible misalignments. That’s nothing in a photo puzzle. But in a gradient, it ruins the effect."

The Play Group opted to work with the best in the industry, and today they are still working with the same manufacturer in Germany, world-renowned specialists who produce every element to to the highest level of quality. But even they initially struggled with the concept and with the precise engineering to get it right. Every decision in this initial phase came down to the minutiae. Even choosing the right stock was important—too glossy and the colours wouldn’t read right; too matte and the image would feel dull. “We ended up working with a very specific paper that could hold rich colour without overwhelming it. It’s not something most people notice, but if you care about how colour feels, it matters.”

The breakthrough came when they started feathering the edges between colours—subtle transitions that made seams less visible. “That tiny decision made the whole thing work. Suddenly it was possible. And beautiful. It felt like a proper piece of design—not just an idea, but an object that worked as well as it looked.”

THE PLAY GROUP'S 1000 COLOUR PUZZLES

Made for People

The first Colour Puzzle wasn’t meant to launch a company. It was only thought of as a self-promotional side project—something to gift to friends, maybe sell a handful of. They made a thousand. It sold out in two days.

“I was on a music video shoot in London and started getting texts from by business partner Jeremy [Wortsman of Jacky Winter]. He told me ‘We’ve sold 500.’ Then suddenly, ‘We’ve got 100 left.’ It was wild.”

People connected with it in a way Clemens hadn’t expected. “It didn’t rely on an image. It just asked you to engage. And the colour—so simple, so bold—it was hypnotic. It gave people permission to slow down. To do something analogue. To sit and focus and feel good about it.”

That response revealed something bigger. The Play Group wasn’t just selling puzzles—it was offering a kind of experience. “People weren’t buying the puzzle because of the picture. There wasn’t one. They were buying it for the process—for what it felt like to do it.”

This opened the door to new ideas. The Play Group started collaborating with artists—Jonathan Zawada, Gemma Smith, and others—creating works that invited slow, hands-on interaction. “Each time we were thinking: what’s the relationship between the person and the object? What makes it worth doing, not just worth looking at?"

"when you’re focused on a shared activity, the pressure to talk disappears, and somehow the good conversations slip in anyway. Or not. Either way, you’ve spent that time together. That’s rare now. And valuable".

Made to Last

The Play Group’s design philosophy is grounded in the idea that the best things are the ones we live with—not just admire. “I’ve never been interested in things that are only beautiful from a distance,” Clemens says. “I want people to use these puzzles. To handle them. To pass them around.”

“Our puzzles and objects are simple, but they’re made to be beautiful and to stay beautiful,” he says. “I want someone to come across one in twenty years and still want to open the box, or hang it on the wall. Not in a nostalgic way—but because it still holds something for them. A memory. A feeling. A connection.”

“There’s so much design out there that’s clever or fast or disposable. I’d rather make something you want to keep.”

This same thinking led to the development of The Play Group’s recent foray into kites. Crafted from recycled sailcloth, these kites are designed not just to fly, but to be beautiful enough to hang on a wall. But again this experience of simple awe and wonder that unites people of all ages and backgrounds.

“They bring people outside. They make you look up. You can’t fly one alone. And when they work—when they lift—that moment of joy is immediate.”

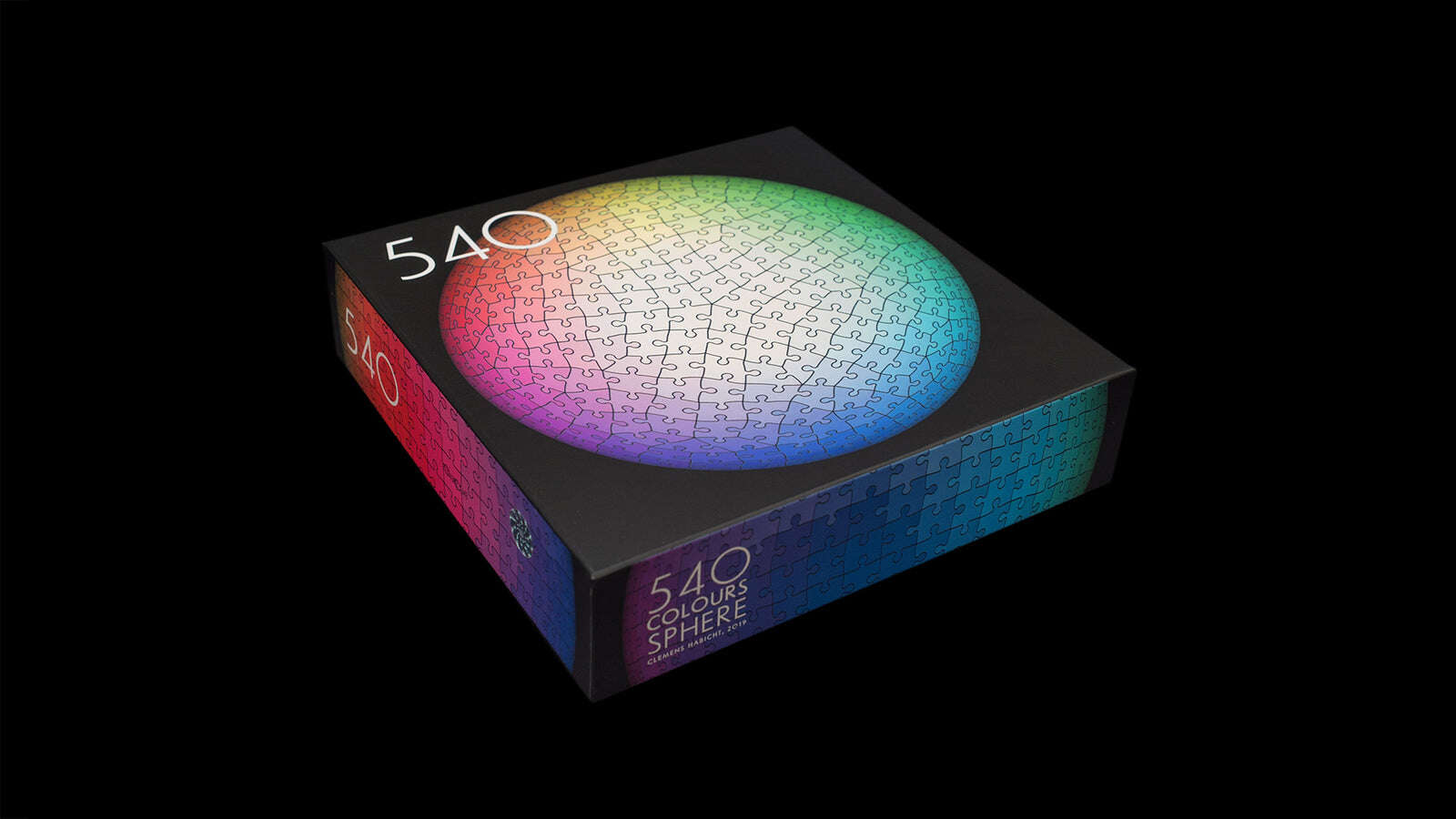

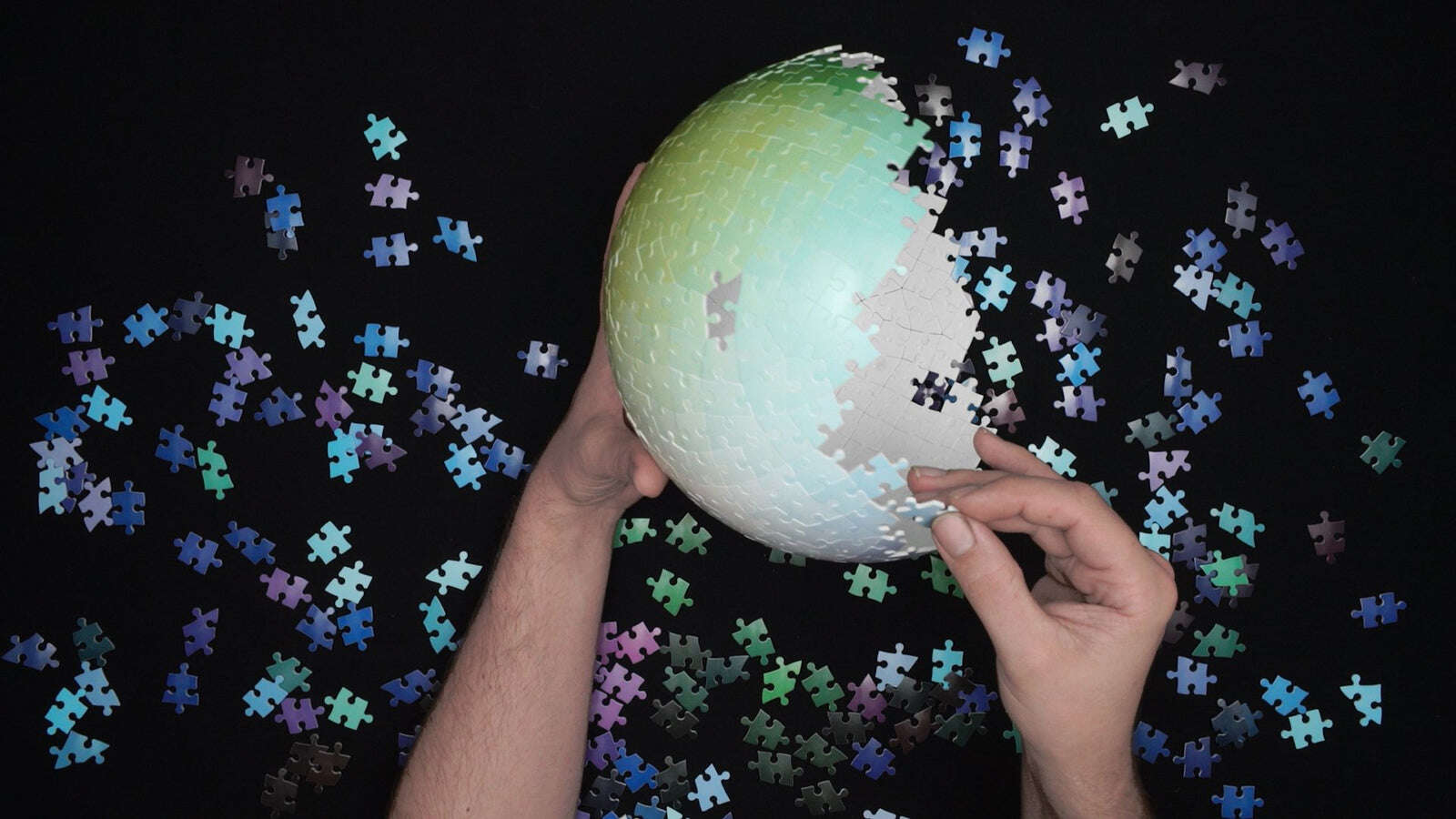

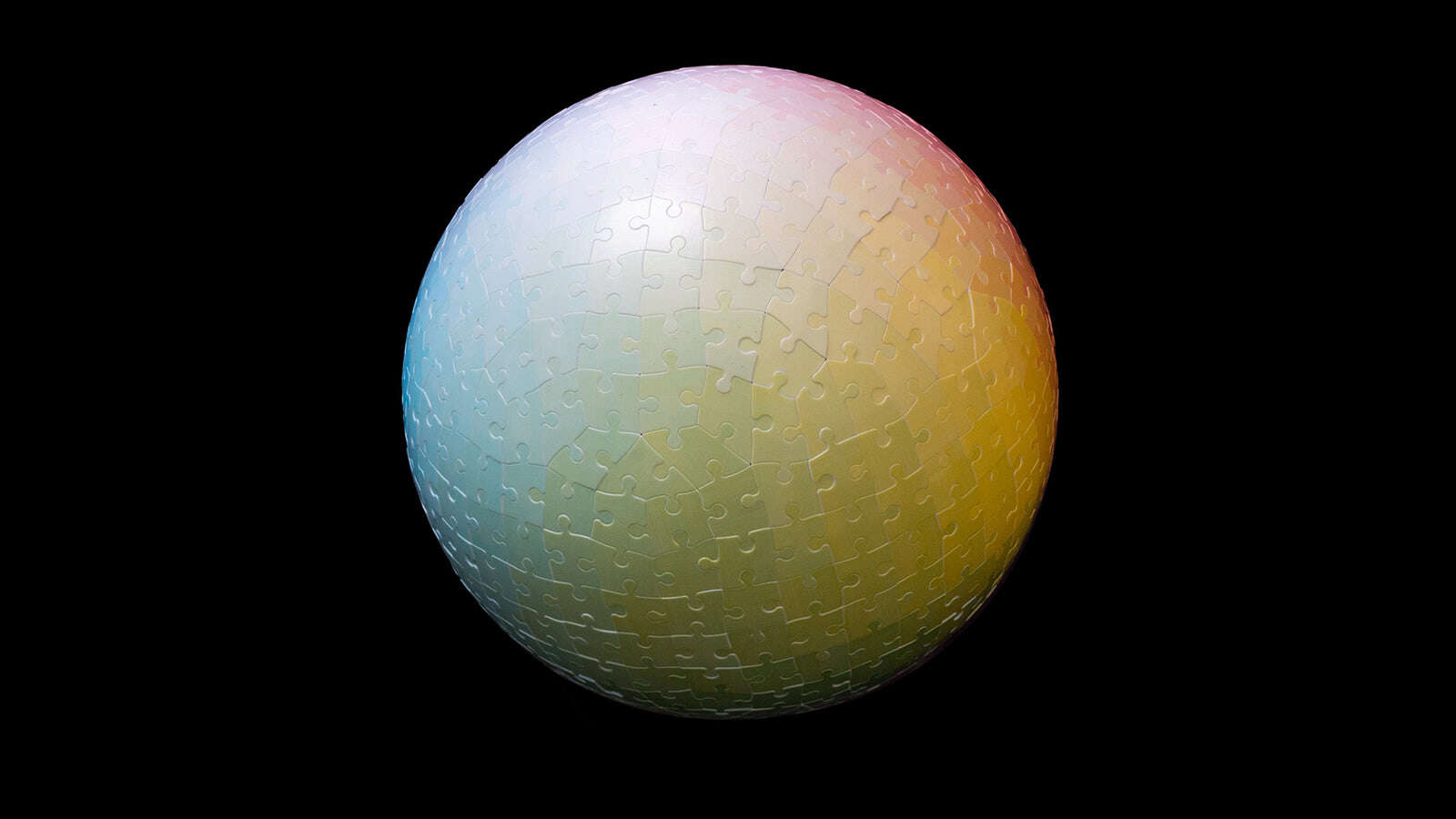

THE PLAY GROUP'S SPECIAL 540 COLOUR SPHERE

"I want someone to come across one in twenty years and still want to open the box, or hang it on the wall. Not because it’s nostalgic, but because it still holds something for them. Because it still invites use. Still holds presence".

The Creative Home

Much of Clemens’s work now happens alongside his daughter. She’s seven, and always drawing. They often work at the same table, pencils and projects overlapping. “She did the typography on a poster for a film I’m working on, and she’s so proud of it. Her handwriting is terrible, but it gave the whole thing this incredible personality.”

“There’s truth in that. A kind of unfiltered creativity.”

He says fatherhood has reshaped how he thinks about design and quality. “I want her to be surrounded by things that are made with care. I’ll buy better food for her than I would for myself. I want her to understand what quality is—not in a snobby way, but in a values way. What lasts. What’s worth keeping. What feels good to hold and use.”

His small family — with his wife, artist Mel O'Callaghan — splits its time between Sydney and Paris. “My daughtere is growing up with two languages, two cultures, two ideas of what home is. And I think that gives her a kind of flexibility. The ability to see things from more than one perspective.”

That duality—between places, between lives—adds texture to the creative work, too.

“In Paris, apartment living is just how people live. It’s normal. Everyone shares space, lives close, walks more. There’s a rhythm to it—a kind of compact intimacy—that shapes how you think about home.

"While I'm there I notice the typography. The signage. The pace. In Sydney, it’s the space, the materials, the sun. So the work shifts, too. But the values underneath it all—slowness, care, togetherness—they stay the same.”

Designing for Togetherness

While The Play Group’s puzzles and objects are made to bring people together and open the door to shared experience, it can’t be overstated just how visually striking and often wildly original they are in their own right. Some challenge the very idea of what a puzzle can be, like a three-dimensional colour sphere; others sit closer to pure art or graphic experiment, bringing bold colour, form, and energy into the home.

“I’m really interested in what a puzzle can look like—how far we can push the format,” Clemens says. “Some of them are these vivid colour fields, others are like sculptural drawings. They don’t just fill time; they fill space.”

Take the Gemma Smith puzzle. It appears almost entirely white—until you begin.

“It’s full of tiny tonal shifts and subtle curves,” Clemens says. “It’s wildly difficult, but strangely compelling. You have to pay attention in a totally different way.”

In the end, whatever form they take—and whatever The Play Group does next—Clemens says it always comes back to the same idea: being together.

“Whether it’s puzzles, kites, drawing, building—these are just frameworks for connection. You sit down, and you’re present with someone, without needing to entertain or impress them. It’s marking time, and that time becomes a memory.”

There’s no prescription—just an invitation. “You don’t need instructions. You don’t need a screen. You just need a table and someone to share it with. That’s what these objects are for. That’s why we make them". So if they become something that stays with you—tucked into a drawer, framed on a wall, passed from one person to another—all the better. That’s the real goal. A piece of time, pieced together.